To celebrate this year’s thrilling FilmFear season, Nuala Shaar – one of HOME’s biggest horror fans – delves into the layered allegorical meanings behind this unforgettable classic…

“In all my years of being exhilarated by cinema, it’s those first curious forays into the horror genre (often when I was underage; being an only child with no curfew will do that for you) that have proven my most intense, affecting and strikingly memorable experiences with the art form. I can vividly recall watching through gaps in my fingers, frozen and aghast, the first time Regan MacNeil’s rickety, sneering head jerked ‘round ‘til her piercing eyes seemingly met my own; this reaction hasn’t tempered much. I still involuntarily flinch at the low, unrelenting growl of Leatherface’s faithful old chainsaw, or the merciless slam of his shiny slaughterhouse door (you know the one). The distinctive sting sound effect from Halloween has, to this day, an instantaneous spine-tingling effect on me – like an aural static shock. These moments spent dicing with this otherworldly and darkly irresistible medium are seared into my memory; they served to define my personal tastes and opened my eyes to the almighty, almost supernatural potential of cinema. Horror’s sinister appeal, particularly that of American horror, lured me in and fostered, early on, an insatiable fascination with film.

“To be sure, I believe the genre holds a special power: to excite and unsettle and overwhelm. But it’s more than that…”

To be sure, I believe the genre holds a special power: to excite and unsettle and overwhelm. But it’s more than that. Though cinema of all forms can take us to extreme places or encourage us to feel more deeply, horror is entirely unique (and therefore valuable, credible and worthy of consideration) in its capacity to translate very specific and complex anxieties or traumas into concentrated visceral experiences. These sounds and images tap into something deep within all of us and elicit primal, physical, fight-or-flight responses – every jolt in your seat or shiver down your spine is the bodily articulation of some deep-rooted fear you didn’t even know you had. Indeed, lauded critic Robin Wood declares the “true subject” of the horror genre to be “the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses or oppresses.” And so, before I introduce this headlining Halloween feature, it ought to be acknowledged there is perhaps no greater trauma in American history than the country’s violent and shameful treatment of BIPOC. This point, made devastatingly clear in recent times, pervades and can be felt in every frame of Bernard Rose’s moving and provocative Candyman (note: mild spoilers ahead).

Tony Todd’s ubiquitous antihero more than holds his own as one of American horror’s most haunting and unforgettable allegorical icons. Based on the equally compelling short story by celebrated fantasy author Clive Barker (The Forbidden), Rose’s 1992 venture follows Helen (Virginia Madsen), a well-meaning but tactless graduate student, as she uncovers the urban legend surrounding the film’s titular character: the murderous ghost of an artist and son of a former slave, lynched in the 1800s after falling in love with a white woman whose portrait her wealthy, racist father commissioned him to paint. Rose relocates Barker’s class-conscious Liverpool housing estate setting to the projects of Chicago and it becomes a whole new story, rich with an insightful social and racial subtext; Candyman comes to represent a personification of the (white) mainstream’s heartless demonisation of Black people, particularly those in the inner cities, whilst Helen’s thoughtless, relentless probing into the lives of the residents of Cabrini-Green (where the killings are taking place) amounts to a keen indictment of the white saviour complex troublingly prevalent in discussions of race.

Initially, Helen is amused by the fantastical tales of the myth. Safe in her plush condo, the brutal murders are merely another unthreatening theoretical concept and fertile ground for a potentially career-making thesis. After all, this commanding, hook-handed figure (his hand was hacked off by the vicious mob who slaughtered him) predominantly preys on the projects, shedding “innocent blood” and slaying decent, honest people and mothers who “just want to raise [their children] good.” However, Helen shortly discovers that her fancy apartment block was also originally constructed as a housing project and converted once city planners realised the development was too close to the wealthy Gold Coast, with no geographical barriers “to keep the ghetto cut off” – with this revelation comes the realisation that the threat may be closer than she (or we) first thought. More than this, we are reminded that her cushy existence is, in effect, an unearned stroke of luck, likely owing to the fortunate circumstances she was ostensibly born into; nothing more, nothing less. It feels like a marked injustice. It is an injustice.

“Whites don’t ever come here except to cause us a problem. So you say you’re doing a study? What you gonna say? That we’re bad? We steal? We gangbang? We all on drugs, right? […] I heard her screaming. I heard her right through the walls. I dialled 911. Nobody came.”

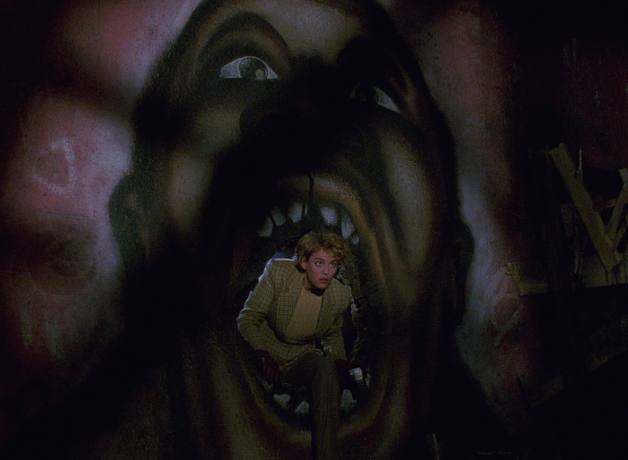

Helen visits the projects for ‘research’, reluctantly escorted by colleague Bernadette (Eve’s Bayou writer-director Kasi Lemmons), where she tastelessly snaps endless photos like a giddy tourist at an exhibit. Further intrigued by graffiti she finds there, she climbs through a hole in the wall to emerge via the open mouth of a mural of a Black man’s tortured face; she will come to inhabit an adverse space sadly frequently occupied by Black men in more ways than this. Notably, both Bernadette and the residents of Cabrini-Green attempt to warn Helen of the dangers of inserting herself where she is, unsurprisingly, unwelcome. “This isn’t one of your fairytales,” Bernadette stresses, “a woman got killed here.” Crucially, it is the victims of the prejudice the myth embodies who fear this spectre of vengeance most of all. By contrast, Helen’s dismissal of the legend as “just a story, like Dracula or Frankenstein,” speaks to her privilege, a fact mirrored by the police’s failure to assist when the residents call 911. “We can’t protect them down at Cabrini-Green,” claims one officer, though he readily comes to Helen’s aid when she is attacked. We are left asking, why? The answer is all too obvious.

It is this tendency to disregard the plight of those in Cabrini-Green that prompts our villain to materialise: “you doubted me […] so I was obliged to come.” “Not content with the stories,” Helen is made an accomplice to his doomed state of eternal persecution and retribution. This destructive, symbiotic relationship is powerfully evocative of the manner in which the trope of the white ‘damsel in distress’ has historically been used to corrupt perceptions of innocent Black men – whereby in life, as in the film, “an entire community [attributes] the daily horrors of their lives to a mythical figure.” Not only does he confront audiences with the violence implicit in the act of Othering a person (or group of people) to such an extent that you barely register their humanity at all, Candyman subverts these roles, framing Helen for the murders he commits. In doing so, he forces her to share in but a sliver of his enormous suffering, (re)creating a version of his demise for her to endure; she becomes a pariah, marginalised, brutalised and incarcerated, such as when she is subjected to a humiliating strip-search. “They will all abandon you,” he asserts, and sure enough, they do.

This terrible yearning to rebuke the world that damned him by instilling fear in its most vulnerable citizens is echoed each time Candyman urges Helen to join him in death, “to live in other people’s dreams, but not to have to be.” “If you would learn a little from me,” he laments, “you would not beg to live,” accepting his gruesome fate as a boogeyman serving to terrify some and condemn others. Upon re-watching the film for this piece, I was most struck by what a heart-rending story it is, despite all the gore. The overwhelming feeling you’re left with as Philip Glass’ stirring, romantic end title rings out is a profound sense of melancholy. It’s rare that a horror film strikes such a poignant chord; not even true love or acquired social status could shield this tragic figure (or his victims) from the ugliness of discrimination. This essential ‘90s classic remains as chilling and brutal a symbolic assessment of self-serving white saviour figures as ever. Like its natural successor Get Out, it’s a film about the horrors of prejudice, but also poverty and marginalisation, and a stark warning of the dangers, even to oneself, of dehumanising people ‘til you can only see them as ‘bad’ or, worse still, you don’t see them – or their suffering – at all. You never know what sort of monster you may become.

If you’re like me, you’ll be excitedly anticipating Nia DaCosta and Jordan Peele’s inspired continuation of the story. Until then, should you wish to summon him yourself, you only need head to HOME on Halloween where you’ll likely find our friend stalking the shadowy aisles of Theatre 1.

So say his name one last time. What’s the matter? Scared of something?”

Words by Nuala Shaar – MA in Contemporary Literature, Film and Theory (Manchester Metropolitan University)

Candyman is showing at HOME on Sat 31 Oct, 15:00.