From Mon 22 Nov – Wed 1 Dec we will be screening three feature films made during Taiwan’s commercial film industry boom, spanning from the 1950s to the 1970s. These films, almost completely lost, have been recovered and restored in a joint project between Taiwan Film & Audiovisual Institute, Kings College London, Ministry of Culture, Taiwan and are now being screened at HOME. In this article, Matthew Carter writes about the history behind Taiwan’s Lost Commercial Cinema: Recovered and Restored season.

In recent years Taiyupian 台語片 or Taiwanese-language cinema have been aptly framed by film scholars as Taiwan’s lost commercial cinema. This somewhat contradictory concept of a cinema being both commercial and inaccessible echoes the ironies and complexities of the Taiyupian and Taiwan’s history in general.

An example of these ironies is the fact Taiyupian refers to films produced in the Taiwanese Hoklo spoken dialect, however, the term itself is Mandarin: “Pian” meaning films and “Taiyu” meaning Taiwanese. This alone is a pretty messy topic as framing Taiyu as either a language or a dialect is contentious to say the least. Despite Taiwan generally being regarded as its own political entity there are plenty of debates regarding its official political status. Language only makes the situation more convoluted, especially considering nation-states usually have languages, yet only regions have dialects.

This sensitive issue essentially began in Mainland China during the late-1940s where the KMT (Kuomintang) or the Chinese Nationalist Party lost the civil war to The Communist Party of China and relocated to Taiwan. The KMT still saw itself as the legitimate government of China and included Taiwan within that broader nation-state – which also meant they declared Mandarin as the National Language or Guoyu 國語.

So, when distinguishing between Taiwanese and Mandarin, it is commonly framed as a distinction between Taiyu and Guoyu. Hence, why referring to Taiwanese as a language and not a dialect can cause complications, as it suggests that Taiwan harbours a claim to nationhood rather than simply being part of a broader idea of China.

When it comes to cinema, taiyupian refers to over a thousand features produced in Taiwan between the 1955 to 1981 by mostly small privately owned studios. The first film was an adaptation of a traditional opera produced in 1955 and became a surprise hit, resulting in numerous studios being established to follow suit. In its most prosperous period between 1965 to 1969 more than a hundred films a year would be produced.

Not only were these smaller Taiyupian studios able to export works overseas and make good money, but the Mandarin speaking cinema produced in Taiwan — which had the full support of the KMT government — struggled to survive.

Taiyupian were known for being primarily commercial products that were put together cheaply in order to make a quick profit. However, as scholars like Ming-yeh T. Rawnsley points out, despite their alleged lower production value, they clearly struck a chord with local audiences to be able to reign supreme in the domestic film market for so long. Also, many filmmakers from the Taiyupian addressed subjects that were considered too sensitive by those working in the Mandarin-Language industry.

Rawnsley also explains that in the 1950s and 1960s specifically, the rise of Taiwanese-language films paralleled Taiwan’s transition from a rural to urban economy, and argues that they articulated and mediated a Taiwanese experience of approaching modernisation. The plot designs and onscreen resolutions to family issues reveal the struggles of the filmmakers and their intended audiences to:

“reconcile different sets of conflicting values in a changing society.” – Ming-yeh T. Rawnsley

Unfortunately, the success of these Taiwanese-language films didn’t last forever, as they were eventually eclipsed by TV and the state-endorsed Mandarin-language cinema. The language was considered to be an uneducated dialect under the National Language Movement (guoyuyundong) and the government wanted to emphasise national heritage over what it deemed local or regional differences.

The lower production quality was also considered to be a factor that compromised the industry’s ability to compete with the Mandarin-speaking cinema from Hong Kong, causing the Taiwanese-language cinema to eventually disappear in the market. The last film was made in 1981 and they were quickly forgotten — the 1980s being the era of the Taiwanese New Cinema, a period when global film scholars were more interested in art cinema.

Fortunately this attitude changed and there is now more scholarly interests in these films. With contemporary scholars being more interested in exploring films beyond their artistic credibility alone, it has allowed these once forgotten Taiwanese-language productions to finally be appreciated for the priceless historical documents they are.

The three films to be screened as part of HOME’s Taiwan’s Lost Commercial Cinema: Recovered and Restored are a testimony to the vast number of genres Taiyupian covered over such a small duration.

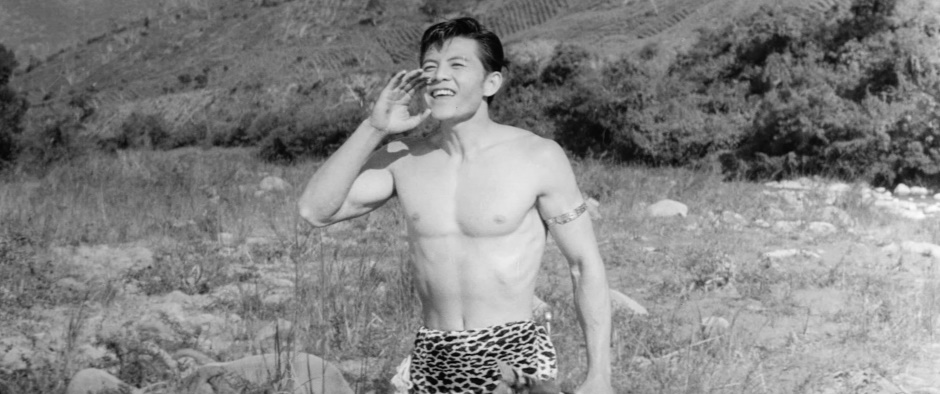

Beginning with Tarzan and the Treasure (Liang Zhefu, 1965), which — if the title wasn’t clear enough — is a Taiwanese take on the Tarzan characterisation. Using popular International themes and character archetypes was common in the Taiyupian, which reflected their global commercial sensibilities. The film’s main plot revolves around an entertaining treasure hunt full of double-crossings and gangsters. Typical of a Taiyupian, the setting is rarely that of Taiwan, but in this case, Macau and the Malaya mountains. The film will be accompanied with a no doubt fascinating introduction by scholar Chris Berry.

The second film is Six Suspects (Lin Tuan-Chiu, 1965), a whodunit where a detective — who developed a speciality in blackmailing people with their shady pasts — is found dead. The five primary suspects have obvious motivations to commit the crime due to the detective’s meddling ways, but they also all have legitimate alibis. The plot takes a turn when a new suspect enters the picture.

The final title Foolish Bride, Naïve Bridegroom (1967) was directed by Hsin Chi 辛奇, who could quite easily be regarded as a Taiyupian auteur. The film is a well-executed rom-com that is progressive on the surface, but quite conservative at its core – a common dynamic with Taiwanese-language films from the 1950’s to 1960’s. Centring on a young couple whose plans of getting married are compromised when their widowed parents’ discover they have romantic history — both believing the other betrayed them many years ago.

Taiwan’s Lost Commercial Cinema: Recovered and Restored season runs from Mon 22 Nov – Wed 1 Dec, at HOME.

For a further look at Taiwanese-language cinema, see more of Matthew’s work here.