Artist Nick Burton’s Our Plague Year was originally conceived as a digital comic strip, before being turned into a gallery exhibition, and now – thanks to Arts Council funding – returning online for more episodes. He spoke to HOME curator Bren O’Callaghan.

Nick, where are you and what can you see – describe your X-marks the spot upon the Earth just now…

I’ve always wanted a library, but I don’t have one. What I do have is a second bedroom that is now a Book Room and Studio. I sit at the same desk, every day, for hours each day and work. To the side of me and behind me are a thousand or so books and comics. In front of me are some notebooks, figures and objects; a Yosemite Sam, a desk calendar of Forgotten English words, some Liv and Dom characters, Quimby Mouse’s Cat Head and a small, glass teddy bear stuck to a square of stone. It has an old, rusty railroad spike stuck through its chest. I call it The Death of Childhood and I like it.

When I approached you to explore a response to the Coronavirus pandemic using a comic strip as your tool, what were your first thoughts?

I was reading about all of the sacrifices people were making to help others (friends, families, key workers, etc.) and so started there. My first thought was a bit ridiculous: it was about a character who helped somebody, sacrificed themselves and died in every strip. It was tongue in cheek and fun, but it didn’t go anywhere. I kept reading, specifically about other plagues, and that’s when I read about Eyam. The parallels with our own situation were incredible and so my second idea was about that – and it’s the one I’m working on.

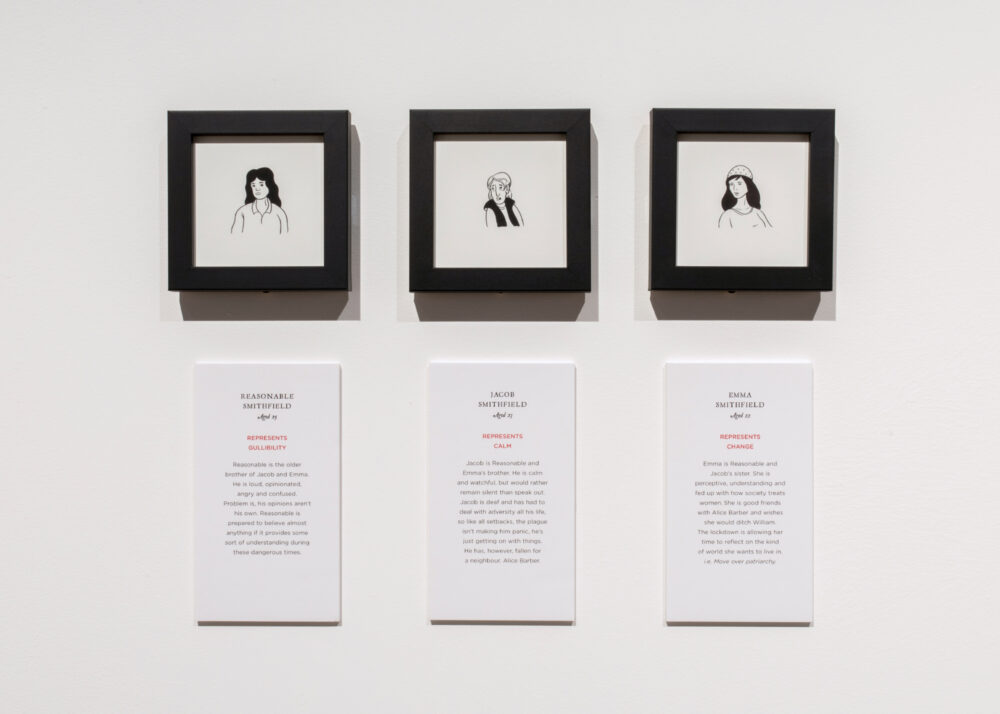

It took me a while to figure out how to tell the story. For instance, is it told by a single person? A family? A bunch of friends? Am I going to use people, or am I going to use animals or insects to tell the story? I settled on people. And I settled on a number of them as I wanted to capture the wide range of responses we’re all having to the same, once in a lifetime (hopefully) event. Once I started, characters began popping up to tell their version of how they’re coping, or not coping, and it felt as though I had something that I could sustain for quite some time. So I ran with it.

Nick Burton, Lucky She’s Already Dead, 2020, archival pigment ink on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper. Photo credit: Lee Baxter

What would you say defines your illustration style and authorial voice, the ‘fingerprint’ that – if an illustration were a crime scene – might show up under ultraviolet light to reveal you as the perpetrator?

The majority of my illustration work is editorial. The style I use for that is simple, colourful and geometric. It’s all circles and squares. People have button noses and round hands. Overall, it’s more pictographic than real. With editorial work I’m always looking to introduce a concept into the illustration, or comic, so that it helps explain the accompanying article as best as possible. The tone of it depends on the article or brief, though I do try to add charm, warmth and a bit of fun to each project.

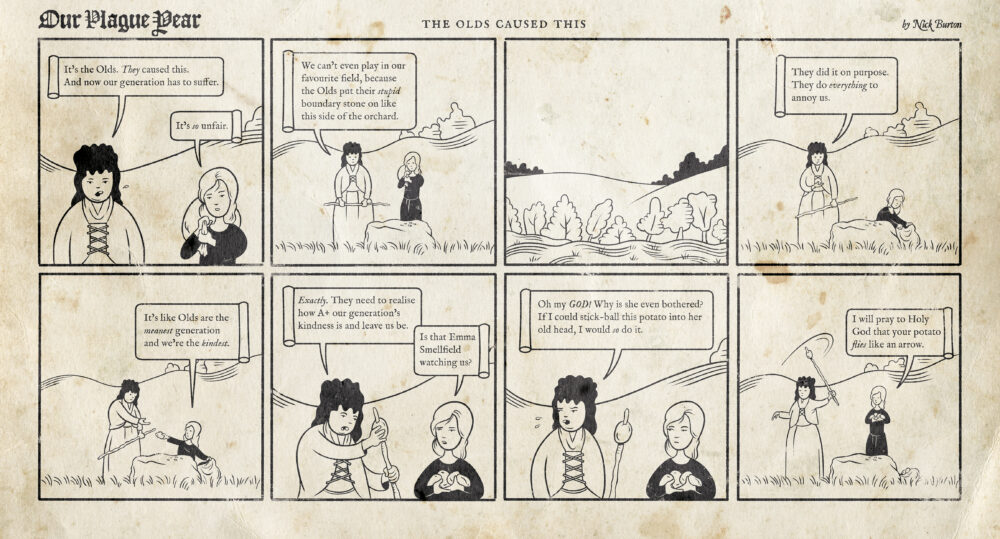

With Our Plague Year, I’m inspired by the graphic language of the 17th century. Old woodcuts, old typefaces, books and advertisements. So I’m drawing from that and trying to make the work feel older and possibly from this time. Having said that, I’m no woodcut artist, but I’m keeping things black and white and trying to capture the overall feel. The style is definitely different from my editorial work. It’s more realistic. It’s still cartoony, but it’s a little more faithful to the world around us. And the hands aren’t circles! With my personal work, the tone seems to always get a bit darker. There’s humour, but there’s also sadness, isolation and loss. Though I do still try to add charm and warmth.

Nick Burton, Our Plague Year title, 2020, archival pigment ink on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper. Photo credit: Lee Baxter

What was it about the story of the Eyam Plague that appealed to you, and how will your approach differ from historical facts?

I’d heard of Eyam, but not in the context of the Plague, and I couldn’t pronounce it correctly. I can now. It’s pronounced Eem – rhymes with Team. Anyway, I was researching for this project and began reading about different plagues. When I read the story of the Eyam Plague, the way it tore through the village, devastated a community, and the incredible sacrifice the people of that village made, I knew there was something in it. Maybe it was because we’d just entered lockdown ourselves and the parallels between what happened then and what’s happening now are considerable.

But Our Plague Year will be significantly different from the true story of the Eyam Plague. It’s set in Eyam. It’ll roughly look like Eyam, and it’ll follow the timeline of the plague in Eyam. But I’m using wholly fictional characters to tell the story. And characters who are not necessarily as selfless as the historical ones we know about. I think of it as an alternative world, Eyam. A world that’s a bit of a mashup with our own (in terms of language and theme) and one that I can play around with somewhat, because I’m not wholly constrained by historical fact.

How important is research to this project -, not only Once Upon a Time, but with application to current behaviours and rolling responses to a 21st Century pandemic?

Really important. I’m reading as much as I can about life during the Eyam Plague of 1665 and about life in general in England during the 17th century. Popular works, obscure works, you name it. And all of it serves as a grounding point upon which to base this fictional narrative. From a modern-day perspective, I’m watching what’s going on around the world (with regards to Covid-19) with a particular interest on how people from different parts of society are reacting to what’s happening in their community. Some people accept what’s happening, while others rail against it. People are generous, people are selfish, some just want to get back to their lives, while others are reconsidering their lives. People are happy. People are angry. People are sad. And it’s probably not much different to how people have always reacted during times of crisis. I want to take these (today’s) reactions and layer them over a similar event from 350 years ago.

I know that you are interested in strange tales of the English countryside, not only factual but also folklore, hearsay and speculation. What is it that fascinates you about these areas?

This comes from a childhood spent reading about and exploring all of these things. Becoming fascinated with the idea that there’s another world just beyond the one we can see. As I grew older, I was equally fascinated with how many of the same tales were told in different cultures – cultures separated not only by geography, but by time. I’m also fortunate enough to have a few friends who are particularly knowledgeable when it comes to British folklore and we head out a few times each year to remote places where stories of otherworldly events might have taken place – recently, or hundreds of years in the past.

In a way, it’s partially what’s interesting to me with regards to this project. An event in a remote, English village, set during a time when folklore, superstition and the possibility of something other were in their final throes as a prevailing cultural thought. And I’ll be making use of this in some of the storylines. Maybe we were capable of seeing things then that we’re no longer capable of seeing. Perhaps we’re a species who’ve lost touch with the natural world. Around this time Robert Boyle founded chemistry, while shortly after, Newton invented gravity, and Edmund Halley figured out the orbit of a comet. It was the dawning of the age of science and the end of the age of magic. Newton, by the way, came up with his law of universal gravitation while under lockdown.

Have you ever attempted a regular, recurring comic strip before?

I haven’t, but I’ve loved plenty of them. I’m thinking of traditional dailies like Peanuts by Charles Schulz, Nipper by Doug Wright, or Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson. More recently, I’ve enjoyed On a Sunbeam by Tillie Walden and Richard’s Valley by Michael Deforge – even though those last two were different than a traditional daily in that they were webcomics that told a single story over a number of months. There’s also Keiler Roberts’ fantastic Diary Comics, the recently concluded Clyde Fans by Seth and Kate Beaton’s Hark a Vagrant from a few years back. The list is endless and Our Plague Year is definitely influenced by a number of them. Especially Hark a Vagrant in that I’m dealing with history as told through a contemporary lens.

As for some of the others, Schulz touched on universal themes that were as relevant to his imaginary world as they were to our (his) real world. Keiler Roberts’ dry wit touches on poignant, funny and honest everyday moments. With Calvin & Hobbes, Watterson wrote about a six-year-old’s childhood. His stories were about imagination, sadness, loneliness, frustration and joy, but also about wanting life to be something more than what it was. Like Peanuts, it was an imaginary world making use of timeless themes.

Richard’s Valley took place in its own, not quite real world. But it commented on events (like gentrification) that were taking place in some of Deforge’s beloved Toronto neighbourhoods. On a Sunbeam was a science fiction coming of age story that spoke to lost love, youth and about trying to survive in a society that doesn’t understand you. It was set far in the future, but dealt with themes and issues that are equally as relevant today.

All of them captured a mood, or an issue of the time and layered it into their storylines. I hope to be able to do something similar with regards to the 1665 Plague and the 2020 Covid-19 virus – highlight themes and responses that are timeless, and show that the way we react today is not so different from how we reacted 350 years ago.

How do you go about sourcing uniquely aged, digital paper? I can’t spot two stains the same!

It’s a time-consuming but straightforward process. The digital paper stock comes from a variety of sources. Many are free downloads, some are bought from stock photo and other sites. Once I’ve added the illustration and text layers, it’s a matter of using masks and levels (in Photoshop) to help make the artwork look like it belongs on the paper. I then add dirt and grunge layers to the file, which helps to vary things up. The final step is to go in manually with a set of textured brushes to remove some of the ‘ink’. To do this, I look where the blemishes are on the paper and then affect the linework in those areas. Once that’s done, I make random touch-ups and scratches until I’m (mostly) satisfied. My goal is for every page to look different. I’m sure I’ll run into similarity issues at some point, but so far so good, for now.

Nick Burton, character sketches, 2020, archival pigment ink on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper. Photo credit: Lee Baxter

Do you have a masterplan for the villagers? What twists can we expect to follow?

There is a masterplan. One that, at the moment, I only know part of. For instance, I know where the story is going and I know how it ends. I’ve noted down some key moments, but I don’t know everything. I will, for the most part, follow the accepted timeline for the Eyam Plague – September 1665 to November 1666, including making use of its peak in the summer of ’66. And I’ll make use of some key locations and events (the boundary stones with the vinegar holes, the religious services in Cucklet Delph and a number of others). As for twists, I suppose they’ll largely be dictated to me by the characters as I continue to write. Will they become better, or worse versions of themselves? And will their relationships change because of this? How will they be affected by events? Who will live? Who will die?

Read the first week of Our Plague Year here and sign up to receive each issue straight to your inbox.