My Missing Valentine screens at HOME on Tue 10 May as part of an ongoing series of Taiwan film events. It’s an example of a kind of Taiwanese cinema that we don’t often have the privilege of seeing in the UK – at least on the big screen – so it’s worth contextualising a little. The plot is best experienced with fresh eyes, so rest assured I won’t touch on the story outside a very brief set up.

You may have attended screenings here at HOME in the past of the taiyupian, Taiwanese-language films that proved popular with audiences between the 1950s and ‘70s. These were locally-focused, commercial films, often made on low budgets and working in well-established genres to provide entertainment for Taiwanese audiences. They gradually faded out into the 1970s for a variety of reasons, an important one being the lack of resources provided by the Kuomintang government. This government was keen to encourage its citizens to identify as “Chinese” and so poured their financial support into Mandarin-language films until the alternatives were squeezed out.

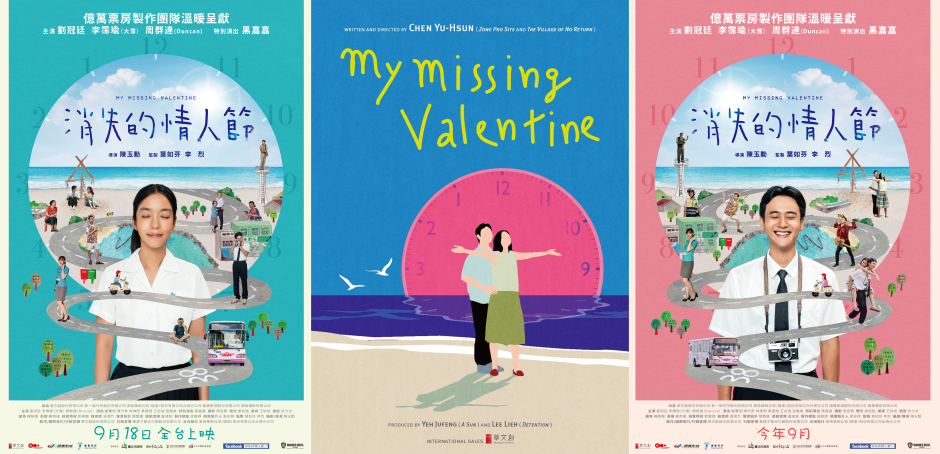

In many ways, the spirit of this film-making is alive and well in the work of director Chen Yu-Hsun and his films like My Missing Valentine. Released in 2020, this is a popular genre film, working to provide local audiences with entertainment while weaving in observations and commentaries around the Taiwanese identity and life on the island at its time of creation. Like those mid-century taiyupian, My Missing Valentine is not an example of that visually austere ‘arthouse’ work of directors like Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Edward Yang, two film-makers who became internationally recognised in the 1980s as leaders of the New Taiwan Cinema movement with whom we are generally more familiar here. No, it’s an example of a much more commercially-oriented, romantic comedy: the kind that Taiwanese audiences are more likely to watch and enjoy themselves.

We begin with Hsiao-Chi (played by relative newcomer Patty Lee Pei-Yu), a post office worker with an intensifying crush on one of her regular customers. For her whole life, Hsiao-Chi has worked so quickly that she seems to exist in a slightly faster timeline than the rest of us. She lives so fast, it seems, that she skips past an eagerly-awaited Valentine’s Day altogether, with no recollection of what happened and an inexplicable sunburn. A rom-com, yes, as much as we might call Groundhog Day a rom-com. While Ramis’ film was initially written as a spec-script designed to be striking enough to get attention from producers, the idea for My Missing Valentine came from a more surprising place: televised sports. When watching lots of baseball and basketball matches during a career dry spell, director Chen saw in the various players the idea that “different people have different rhythms” in how they experience the same events. Compelled by this realisation, he endeavoured to turn it into a film – adding a supernatural twist to an otherwise formula-faithful genre.

As unlikely a set up this may seem, it isn’t particularly new territory for the director, who is known in the region for his ability to weave high concept meditations and musings on Taiwan’s contemporary issues through genre cinema. Through comedies, in particular, Chen has offered numerous investigations of time, place, and cultural memory in his feature films. He started his career in television in the 1980s before moving to film work in 1994 with the equally well-respected Tropical Fish, a comedy about a mishandled kidnapping of a young boy that raised questions about Taiwan’s school system, urban-rural divide, and labour migrations. Despite landing well with critics, both Tropical Fish and his second, Love Go Go in 1996, were box office disappointments. It was around this time that Chen penned a first draft of the screenplay that would go on to become My Missing Valentine , but it never saw the light of day at that time because the director felt so badly about the box office performance of his first features that he quit cinema altogether.

He believed that he had ‘failed’ the legacy of New Taiwan Cinema – whose artistic rigour he admired – and took solace in the world of TV advertisments for the next 10 years. This history is worth knowing because it lays the foundations for what we see in My Missing Valentine. There’s a certain rhythm to My Missing Valentine that seems to hold one foot in that commercial sensibility. It took Chen 6 months to edit the film with his editor Lai Hsiu-hsiung and the director reflects on this process as being a battle between the latter’s eye for sentimentality and Chen’s own eye for fast-paced comedic timing. What they ended up with was a productive balance somewhere between the two – allowing space for melancholy and reflection within the slapstick goofs and visual gags.

This accomplished editing was one of many elements of the film that received recognition at Taiwan’s influential Golden Horse Awards. My Missing Valentine was nominated 11 times at the 2020 edition, winning 5 out of this sweep including the award for Best Picture: the first comedy to do so since Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle in 2004. It’s an emblematic example of the kind of popular cinema produced in Taiwan that critics deem substantial enough to warrant attention and accolades normally kept aside for ‘auteur’ directors and more challenging social productions.

That’s not to say that all of Chen’s work hits on all fronts, or that the film was universally well received in Taiwan, and what is perhaps most interesting about My Missing Valentine are its missteps. While its presentation is light, accessible, and certainly enjoyable, it raises some quite knotty questions around consent and privacy that don’t seem to have been intended by its creators. Alongside the critical acclaim it received at the Golden Horse and other global award shows, there has been an equally strong critique of the film and its uncritical representation of dating – or the pursuit of a partner – that what might call ‘stalkerish’. Indeed, when the film released in Taiwan a reviewer for the Taipei Times found it emblematic of how ‘Taiwanese movies and dramas still continue to perpetuate the unrequited stalker stereotype as a viable way to win someone’s heart’. Legislators in Taiwan were still pushing for stalking to be considered a criminal offence as recently as 2021, so there are serious questions to be asked about the role of a film like My Missing Valentine and its contribution to social discourse in the country. The screening at HOME will be followed by a panel discussion with curators Rachel Hayward and Andy Willis where some of these questions can be raised and discussed collectively.

If anything, these stumbles make My Missing Valentine all the more interesting as a film. It builds on director Chen’s experience of working social critique into films which, on the surface, are more light-hearted comedies (even if its social commentary may have been unintentional, this time…). It’s a fascinating insight into Taiwan’s popular cinema, a kind which leads the box office there but rarely makes it abroad, giving us a wholly different picture of the island to the filmmakers we are used to seeing.

By Fraser Elliott

Fraser is Lecturer in Film, Exhibition Curation at the University of Edinburgh and also a member of the Chinese Film Forum UK. Before moving to Edinburgh he was a member of the film team at HOME.