“In the night, a thick tangled root had grown from the boys navel, and a tough fleshy root had grown from the girls navel, and these roots were connected to their mothers navel, rooting the three of them together. They tried to cut the roots. But they could not.”

Sitting on a shelf in the British library is an unassuming red book. Indispensable to folklorists all over the world, the Aarne index has categorised and numbered thousands of folktale types. From men outwitting the devil to tales of foolish wives, from tricksters to magic animals, and tales of stupid husbands, the list goes on.

The idea for ‘roots’ began with this book. I was researching folk tales, with the aim of finding some stories to stage. The Aarne index is a treasure trove as a theatre maker, filled to the brim with great ideas, very silly ideas, and very, very weird ideas. I would pick a category in the book, for example ‘Transformations’ under which would be titles such as ‘Man turns in to melon seed’ ‘Woman turns in to pestle and mortar’ and then, based on the title, or on a two line description of this type of tale, I would write a short terse story.

I attempted to stick to the original format of these tales as I had read them in Angela Carter’s anthology of female led folk tales. They were free of florid language, blunt, odd, and very appealing to the 1927 sensibility. I rather liked the idea of not moralising with these stories and had to fight my own instincts to right the wrongs of these tales, to tame them. Rewriting history is very dangerous, perhaps not only in fact but also in fiction. After writing the tales I would read them aloud, often to a liquor-imbued crowd of friends and family, and see how they reacted. Esme and Paul of 1927 would listen to them and try to visualise how to stage them, if they liked the tale it went in to a pile of ‘potentials’. I hoped that a nice clean, clear-cut, very cohesive theme would emerge from these stories…

When Italo Calvino compiled his book of Italian folk tales, he was searching for Italian stories, when Carter compiled her book of folk tales, she limited herself to tales with a female protagonist.

I hoped for something similar. But nothing of the sort happened. We ended up with a rather ragtag collection of folk jokes and stories that we all liked…just because. These stories were not character driven, not psychological, more like one-liners, folk jokes, and yet they seemed universal also, they could all be applied to real world situations. They were matter of fact, lacking a clear moral, and different to the folk tales we grew up with, which, it became clear, had been bleached and cleaned up, trimmed and neatened, packed full of Christian morality, gender stereotypes, and ‘defanged’ to quote Carter, whose own anthology of folk tales begins with an Inuit tale about a woman who arm wrestles men in to submission, Oh, and then shows off her huge clitoris.

We kept coming back to certain questions with these stories, and they are still, for the most part, unanswered.

What do the stories of our forbears tell us about ourselves? What can we learn about how to tell stories now, for future generations, from such stories?

Underlying our exploration in to folk tales was our imminent departure from the EU, and this couldn’t help play in to our thinking about the show. We take our stories with us wherever we go, stories migrate, and they have no respect whatsoever for boundaries and borders. What I found in the Aarne index, was that there was no real link between a story and where it was found. (The index tells you beneath the tale where the tale was found, for example, one story might have been found in Lithuania, and Ireland, Slovenia and Portugal). There were no clear-cut differences in the stories told in Scotland and in Spain. Luck, ill fate, love, greed, magic, more greed, animals, parents, sex, death, did I say greed? These themes cropped up all over the world, cultural variants, yes, but the same stories, planted all over the world, flourishing, mutating, morphing, splicing, combining with other stories.

Having selected a bakers dozen of tales we started to give them all the 1927 treatment…though some of these tales would not be tamed. In reading them aloud, I noted that my own ‘trained’ voice struck me as insincere, too theatrical, and it sounded wrong. We thought initially that we would try to stage them without words, then someone hit upon the idea of asking a couple of friends to read them, what would they sound like in the mouths of non actors?

The first story we tried was a tale called ‘The luckless man’. We gave it to a friend, Nigel, an ex steel worker turned Councillor from Port Talbot in Wales. He read the story wonderfully (it is still my favourite delivery in the show) and we were sold on the idea instantly. Other friends and family started popping to mind when we looked at the stories, again, the logic of our choices wasn’t always that clear (are many choices clear and logical?) A voice would just come to mind and we’d ask a friend to record themselves speaking the story.

We invited a group of friends to our studio in a freak snow storm in March, cooked them all an Irish stew in a pot as big as a bath tub, lit the candles, and handed the stories out to be read by a multitude of different voices.

Food and stories kept crossing over in this process. One of the tales ‘Snake’ was read by Paul’s brother’s wife’s Mother.

She cooked us a feast, flitting about the kitchen telling us her own stories, about her time in India, Italy, Africa, North London, her nursing career, her love of cooking dosas. The act of sharing stories, seemed to encourage people to share their own stories, without prompting, and we started documenting the storytellers and their own tales.

Sitting around a table sharing tales invented, tales from our childhoods, real life stories, ancient folk tales, all mingling with a healthy disrespect for fact and fiction and indeed time. The immortality of stories, their ability to reinvent themselves. It made a change from looking at each other’s photos on the tiny screens we covet in our pockets.

Musically we had all wanted to move away from the wonderful but rather static piano. We wanted to explore portable instruments in our animated onstage world, and instruments that called to mind folk tales. Fran and Dave appeared in our midst; they responded to Lilly’s piano music with invention and playfulness, and turned simple tunes in to something otherworldly.

In their audition Dave played coca cola bottles, a donkeys jaw, bones, a dulcimer, drums, bells, whistles, and a nose flute whilst Fran accompanied with virtuosic violin, viola, and two recorders at the same time. So we had our ingredients, and we started mixing them together in the rehearsal room.

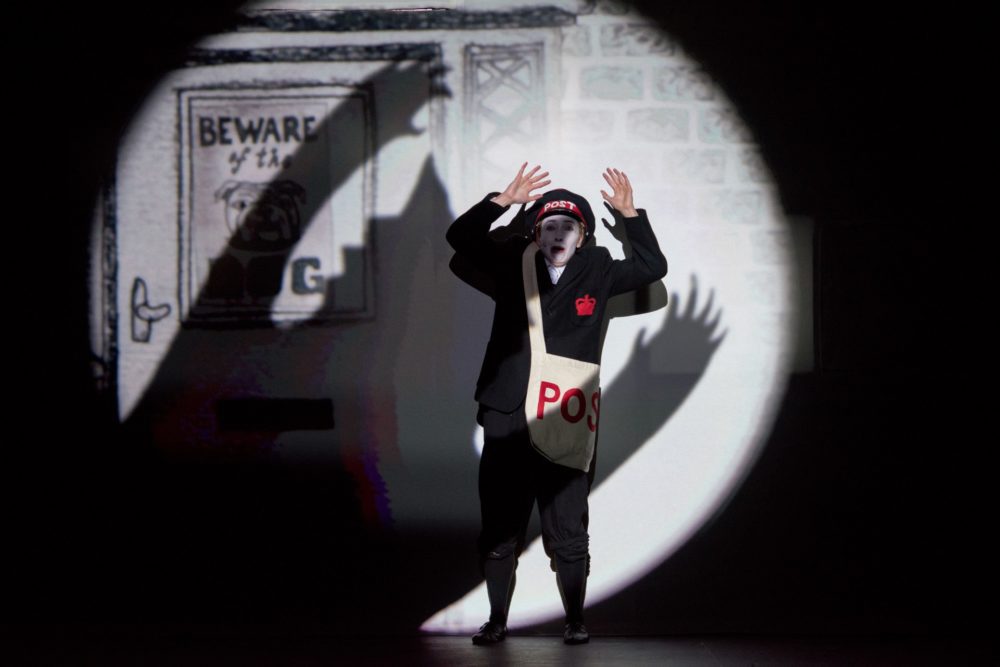

Whether the combination of live music, pre recorded stories voiced by non-actors, animation, acting and live dialogue would work, we didn’t know. These stories, found in a folktale database, that very likely never thought they would see the light of day, let alone be tinselled and tarted up by 1927, suddenly started hobbling in to existence, at times a little gauche, a little shy, but gradually they started to become living breathing stories. As they once would have been. A hodge podge of tales told using all of the tricks at our disposal.

And now we plan to present them to people around the world and hope they spread a little joy, prompt memories of folk tales told to us as children, of forests and talking animals, of proverbs and one liners told to us by aunties and teachers, nurses and shopkeepers. We hope this show will tease out new stories, take root in the audiences imagination, and perhaps even prompt people to interrogate the stories we are spun by Hollywood, to contemplate the very nature of narrative, to question the authority of the author, and most importantly, to listen to one another’s stories, to really, listen…

Suzanne Andrade, June 2019

Roots is at HOME from Wed 11 Dec 2019 – Mon 30 Dec 2019