“Quentin Tarantino is interested in watching somebody’s ear getting cut off; David Lynch is interested in the ear.” – David Foster Wallace

“Now if you’re playing the movie on a telephone, you will never in a trillion years experience the film … You’ll think you have experienced it, but you’ll be cheated. It’s such a sadness that you think you’ve seen a film on your fucking telephone. Get real.” – David Lynch

As a publically-ousted cinephile, one of the most frequently-asked [and utterly asinine] questions I find myself being posited on a semi-regular basis, usually by some distant relative attempting to feign interest in my foolish life-choices over plates of cold-cuts and devilled eggs at some tenuous/pseudo-religious family gathering, is:

“So, what is your favourite film?”

Now, after years of admittedly disproportionate belligerence on my part in response to this idiotic line of inquiry, in a last-ditch attempt to curb my rapidly spiralling misanthropy and reduce the number of violent interactions I am directly responsible for, both physically and emotionally, I feel I have mustered a sufficiently diplomatic response to this brain-boilingly stupid informational request:

“I don’t have a favourite film, Auntie Ida. But I do have a favourite film to watch in a cinema.”

By stripping away the pressure of having to decide upon a singular, absolute, qualitative zenith from the entire totality of the cinematic art form – my preferred of all the expressive mediums – and instead focussing on the pleasure derived from the spectatorial experience of consuming a film in an actual bonafide theatrical exhibition-type environment, I’ve found I can supply an honest and simple answer:

“David Lynch’s Lost Highway (Asymmetrical Productions, 1997)”

Lynch has always considered cinema to be 50% sound, which is not only accurate on a strictly sensory level, but probably also why intricate, complex sound designs have always been so central to his filmic works. Ever since his debut feature Eraserhead (1977) – during which he embarked upon a ground-breaking collaboration with the Berkeley-born coke-bottle-lens-bespectacled auditory genius Alan Splet [who reportedly also turned Lynch onto Transcendental Meditation, another formative influence upon his life and working practice] – Lynch has crafted some of the most detailed, iconic and immersive soundscapes ever committed to film.

The protracted five-year-long production cycle of Eraserhead – shot almost entirely in the deserted basement of the inaugural American Film Institute campus, a decaying mansion in the Hollywood Hills – saw Lynch and Splet use eccentric, home-made, pre-digital analogue techniques to create a dazzlingly industrial cacophony that plays no small part in the nightmarish originality of this singular debut, which became a cult hit on the midnight screening circuits amongst stoned college students [although the prospect of watching Eraserhead whilst stoned exceeds the limits of my cinematic courage] and even caught the attention of Mel Brooks, who subsequently hired Lynch to direct The Elephant Man (1980).

What could have easily been a tasteful but rather stately historical rendering of the life and times of John Merrick, set in the foggy monochrome milieu of Victorian London, became infused with a truly disturbing sense of the surreal as Lynch injected nightmarish Freudian dream sequences of Merrick’s mother being trampled [perhaps even raped] by a giant stampeding elephant – again collaborating with Splet to create some reverberated screams that still ring in the ears long after the credits roll. Without this primal articulation of Merrick’s tortured psyche, more monstrous and upsetting than any physical deformation could ever be, we would lack the heart-breaking empathy with and deep understanding of the character’s final decision, and all the agony he had endured.

Whilst his big budget space-opera Dune (1984) remains, much like a Seder hosted by Wittgenstein, a misstep we must mostly pass over in silence, it is notable that a crucial element of the film’s labyrinthine plot – rendered essentially incomprehensible by savage studio-enforced cuts to the running time [Lynch would never again sacrifice final cut over one of his films] – is that a fresh-faced Kyle MacLachlan literally weaponises sound via megaphone/ray gun-type devices in his quest to lead the Fremen to victory over the tyrannous House Harkonnen in the climactic battle on the desert planet Arrakis. Despite the crippling multitude of external pressures and creative restrictions that robbed Lynch of the ability to craft the film in his usual indelible style, he still managed to find a way to make sound central to the action. The giant sand worms, killer Toto soundtrack and Sting’s shaved armpits also make the film more than tolerable.

Returning to more intimate production conditions with Blue Velvet in 1986, Lynch struck a deal with producer Dino De Laurentiis [whom must have been frantically second-guessing his decision to hire this “Jimmy Stewart from Mars” for a three-picture deal after the economic fallout of Dune’s colossal commercial underperformance, with two more films still to go] – they agreed that Lynch could regain final cut and creative control over his next project if he worked within a modest budget and sacrificed much of his director’s fee. The result, not without a strong sense of irony, was Lynch’s most commercially-successful feature and arguably his most fully-formed and critically-admired film to date.

Reuniting with cinematographer Fredrick Elmes – who shot Eraserhead – as well as sound designer Alan Splet and leading man Kyle MacLachlan, Lynch set out to reconstruct the close-knit, collaborative production environment that marked his debut masterpiece with such out-of-absolutely-nowhere-else-on-earth originality. The soundscapes devised by Lynch and Splet in Blue Velvet, that absorb the audience into MacLachlan’s descent into the sadomasochistic underbelly of small town suburban Americana, are remarkable not just because of their terrifying sensory violence – roaring sound collages one could spend an unhealthy amount of time trying to deconstruct – but also because of their immersive ability to suck the audience into the character’s tortured psychological landscape and make them feel complicit in his dalliances with the darker side of human interactions. This, combined with Angelo Badalamenti’s haunting, uncanny, dreamlike score – the beginning of another collaborative relationship that would last a lifetime – make Blue Velvet a feast for the ears [no pun intended]. It is also in this film that we first encounter one of the most defining Lynchian tropes: character’s singing and lip-synching to popular ballads and crooners. Be it lounge-singer Isabella Rossellini’s spot-lit renditions of Bobby Vinton’s titular song or a make-up clad Dean Stockwell mouthing the lyrics of Roy Orbison’s “Crying” into a work lamp for Dennis Hopper’s perverse amusement [admittedly far from the worst of the psychopathic Frank Booth’s predilections], the trope of the filmed musical performance is so prominent in Lynch’s work that it later became a weekly staple of Twin Peaks: The Return. Just as the narrative marks a coming-of-age for the virginal Jeffery Beaumont, so too was Blue Velvet the point at which Lynch the filmmaker fully flourished, growing into the artistic confidence that has defined the rest of his career.

Rather than chronologically trudging through the rest of Lynch’s cinematic and televisual oeuvre, noting various moments of auditory interest – which would be as boring for you to read as it would be for me to write – please just rest assured that Twin Peaks (1989-1991), Wild at Heart (1990), Fire Walk with Me (1992), Lost Highway (1997), The Straight Story (1999), Mulholland Dr. (2001), Inland Empire (2006) and the triumphant Twin Peaks: The Return (2018) [the first line of new dialogue being, after a 25-year hiatus, quite literally: “Listen to the sounds.”] all place as much importance on their meticulously constructed soundtracks as they do to the director’s inimitable visual aesthetic. Even the short-lived and rarely-discussed sitcom On the Air (1992) – David Lynch and Mark Frost’s abortive follow-up to their network television coup Twin Peaks – derives much of its strained humour from conversational miscommunications due to thick foreign accents and hearing impediments [deafness being another returning motif in Lynch’s work, one of the worst afflictions his characters can endure]. Hopefully it will be more interesting to end this piece by taking a brief look at why Lynch’s dedication to the equality of sound and vision in his filmmaking practice makes it so decidedly cinematic.

Lynch argues that you haven’t experience a film if you’ve watched it on your iPhone; I’d go even further to say you haven’t experienced a David Lynch film until you’ve seen it on the big screen. Even with the technological advancements in home entertainment viewing – your 65” 4K Ultra HD TV with Triluminos Display certainly makes the latest episode of Game of Thrones look better than those decayed VHS recordings of Seinfeld rotting away somewhere in the attic – unless you are fortunate enough to have a Glastonbury-level sound system installed in your living room, when it comes to the cinema of David Lynch if you’re not watching it literally in a cinema you’re missing out on half the ride.

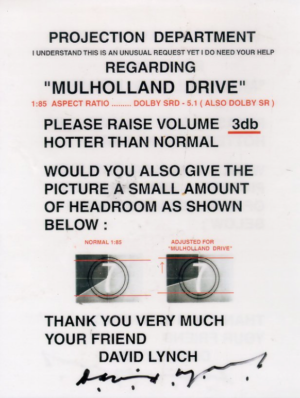

The 2001 masterwork Mulholland Dr. remains a staple of the repertory cinema circuit, and, much like Kubrick’s sci-fi masterwork 2001, if you book the film on a 35mm print – as I was want to do during my youthful misadventures in exhibition – the stack of celluloid reels comes accompanied by a note to the projectionist, signed by Lynch himself, that reads:

Now this attention to detail, this awareness of the precise expertise required and human labour responsible for presenting a film in the manner intended [i.e. the Projectionist – that dying profession which if ever fully extinguished will make us all the poorer], is incredibly rare nowadays. It conveys the message that this is an artist who wants you to experience their work under very specific conditions, and knows exactly what those conditions are, and anything other than those conditions quite frankly doesn’t cut the mustard.

By this point in my life I’d watched Lynch’s post-modern film noir Lost Highway innumerable times, on DVD. I was too young to catch its [short-lived] theatrical release in 1997, and the commercial disappointment of that run mean that no one was bothering to renew the theatrical rights to the film and there were no locatable 35mm prints in the UK. After several years of detective work [which could have been achieved by simply looking on the back cover of the aforementioned well-used DVD copy] I discovered the European sales agent and got in touch to see if they still held a celluloid print. Eventually I received a fairly curt response confirming that yes, they still held the film, in good condition, and as long as we paid the hefty license fee and all transportation costs to get the print to and from a warehouse in Paris it was all ours.

I believe my previous employer has yet to forgive me for the costs associated with this endeavour but, as they say at French Sales Agencies on Edith Piaf karaoke night, “je ne regrette rien”. It was worth all the financial chastisements in the world. To watch that film projected on the silver screen, blasting out 3 decibels “hotter than usual”, the bass jiggling 250 bodies in perfect unison, that was my favourite cinema experience. It was like watching an entirely new film – elements in the soundtrack I’d never heard before suddenly swirled in my inner ear; Barry Adamson’s delirious jazz-compositions spiralling down the snail-shell of my Cochlea; the dark corridors into which Bill Pullman and Balthazar Getty dissolve were blacker than black, total darkness, not some milky grey sheen but a true absence of light. And, without giving too much of the plot away, let’s just say that the final moments of the film – when presented at the volume levels Lynch intended – are both metaphorically and medically “head-splitting”. Pure bliss.

James King