To coincide with our film retrospective Jarman at HOME, HOME Creative Director: Film & Culture Jason Wood reflects on his life and work.

This is approximately a 15 minute read.

—–

Born Michael Derek Elworthy Jarman in Northwood, Middlesex, on 31 January 1942, Derek Jarman attended Kings College, London and the Slade School of Fine Art. His art studies can be traced through to his later aesthetic, but his first work in cinema came when, after a period working in theatre design, Jarman was invited to work as a set designer on Ken Russell’s The Devils and Savage Messiah.

Having begun making his own experimental films on a Super 8 camera in the early 1970s, Jarman’s first feature film was the low-budget Sebastiane (1976, co-director Paul Humfress), shot in Sardinia for just £30,000. Set at a military outpost and concerning St Sebastian’s martyrdom and denial of his love for his commanding officer, the film forged a template for Jarman’s subsequent career, focusing on an outsider figure. Sebastiane’s denial conflicts with the film’s overall aesthetic and emphasis on homosexual imagery – another constant in Jarman’s artistic output. Well received by critics, Sebastiane also sparked controversy for reportedly being the first British film to feature an erect penis.

Jarman’s next venture, Jubilee (1978) enjoyed the distinction of a Parliamentary mention. A fiercely anti-establishment work that depicts a post-punk vision of a social wasteland, the film follows Elizabeth I and her court astrologer John Dee as they travel forward in time to contemporary England. Made in the wake of Queen Elizabeth II’s silver jubilee, it is an outspoken, angry and urgent vision of a country searching for modemity but mired in decline.

Working with Super 8 and 16mm film throughout this fertile creative period (the two formats would be cut together and then blown up into cinema formats), Jarman produced a series of shorts that later became In the Shadow of the Sun (1972-74), manipulating the film image and setting it to a post-industrial soundtrack. This desire to experiment with sound and image would retain a central prominence in Jarman’s future output. The Tempest (1979) was a startlingly bold Shakespeare adaptation that offered an irreverent interpretation, foregrounding the relationship between Ariel and Prospero. Filled with contemporary allusions, the themes of banishment and enslavement later reappeared in The Angelic Conversation (1985), a film in which the imagery is accompanied by a soothing voice reciting a series of Shakespeare’s sonnets, obviously chosen for their openness to a homoerotic re-reading. Continually contrasting sound and image and illustrating the director’s ongoing unease with conventional narrative, the film was frequently cited by Jarman as his most cherished work.

Jubilee (1978)

The advent of Channel 4 funding in the mid-1980s ushered in a new era of internationally distributed low-budget British art cinema. This favourable economic and cultural climate allowed Jarman to establish a reputation as a radical and profoundly influential auteur. The director later resisted this radical labelling, seeing himself as working more in the arch traditionalist vision of figures such as William Blake. In 1986, after years of trying and failing to secure financing, Jarman finally realised his dream of bringing Caravaggio (1986) to the screen. A pastiche period biopic based on the life of Baroque Italian painter Michelangelo da Caravaggio, the film is a skilfully realised and vividly shot tale of art, power, sexuality and their interconnections. Complexly irreverent, the film offers a clear example of Jarman’s disregard for convention, playfully introducing anachronisms such as a motorbike and, in a superlative touch, a critic who writes his barbed responses to Caravaggio’s work on a typewriter. Funded by the BFI and produced by Colin MacCabe, it arguably remains Jarman’s most famous and widely seen work.

The interplay between history and modernity is also foremost in The Last of England (1987) a collage of Super 8 films which delivers a harsh judgement on the Thatcherite politics of the late 1980s; the title ingeniously reinterpreted Maddox Brown’s famous painting of emigrants leaving the English shores for a life in the New World. The film has been compared to Humphrey Jennings’ documentary Listen to Britain (1942), its very antithesis. Where Listen to Britain indulges in the idyllic, The Last of England exposes the decay. The film sparked huge public debate, with the historian Norman Stone labelling Jarman’s vision of England as ‘sick’. Jarman conducted his defence through the pages of The Times, defending the film as an accurate reflection of life in Thatcherite Britain.

Tilda Swinton in Caravaggio (1986)

Announcing publicly at this time that he had been diagnosed as HIV positive, Jarman became a spokesman against what he perceived to be repressive anti-gay politics and something of a fly in the ointment for the political establishment. Diversifying into other media, Jarman produced a series of pop promos for artists such as The Smiths, published some well received monographs and moved to Prospect Cottage, a fisherman’s cottage in Dungeness, on the Kent coast, where he cultivated his unique garden.

Shortly after his diagnosis, Jarman directed War Requiem (1989), a film version of Benjamin Britten’s musical treatment of Wilfred Owen’s war poetry. A moving plea for peace that eloquently speaks of the tragedies of war, the film has also been read as a metaphor for the impact of the HIV virus. Filmed at his cottage, The Garden (1990) was an entirely non-narrative piece, which metaphorically suggested that Britain had become a neglected garden. Full of striking imagery, the film also deals more explicitly with Jarman’s illness, the persecution of homosexuals and the director’s ongoing battles with the powers that be.

The Garden (1990)

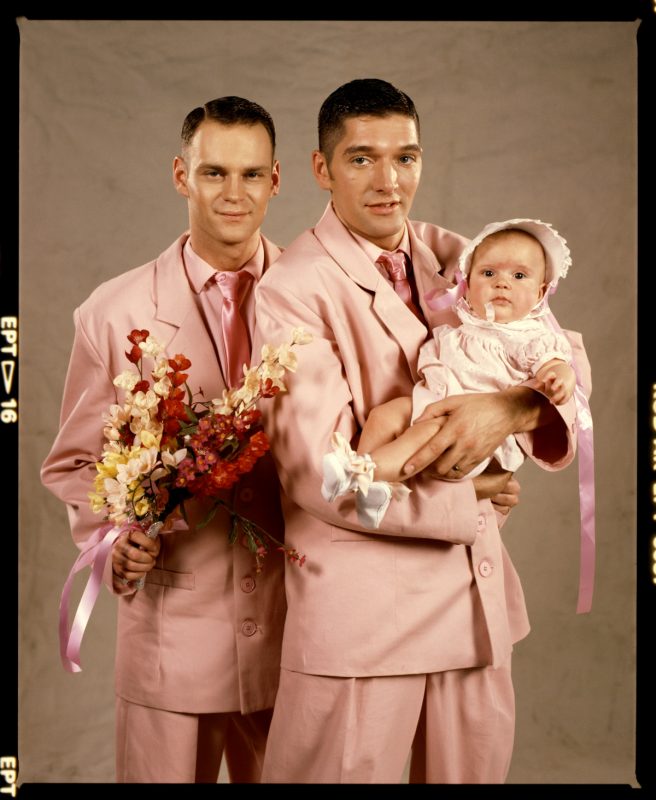

Mixing contemporary politics with history, and featuring footage of an anti-Clause 28 demonstration by OutRage!, Edward II (1991) marked a bold adaptation of Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan drama. Drawing upon his theatre-design background for the film’s unconventional staging, Jarman also combined pop-video aesthetics and poetic dialogue in an examination of misogyny, political violence and the sexual oppression of the homosexual king and his followers. Acutely aware of his deteriorating health, Jarman swiftly set to work on a more conventional biopic: 1993’s Wittgenstein, a droll account of the life and work of the great philosopher co-written with Terry Eagleton. The studio-based production employed props, sound effects and lighting to suggest changes in location, again harking back to Jarman’s art-and-design training. The film, though punctuated with moments of humour, is most adept in terms of capturing Ludwig Wittgenstein’s enormous intellect and existential angst.

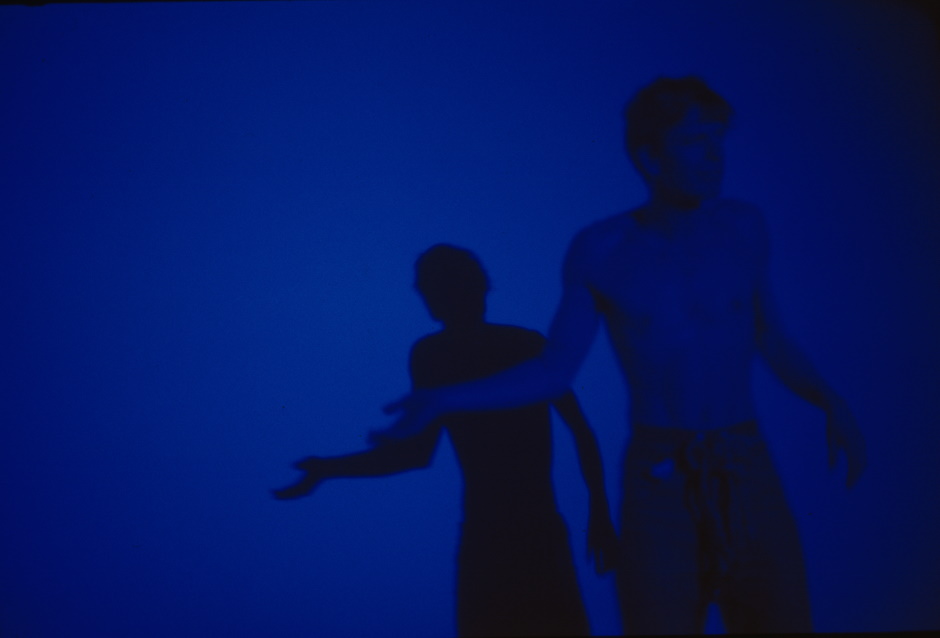

Blue (1993) is perhaps Jarman’s most striking and experimental film. A metaphorical reflection of the blindness caused by his illness, it features a blue monochrome surface inspired by French painter Yves Klein, accompanied by Simon Fisher Turner’s synthesised score and a tide of voices that includes key artistic collaborators Nigel Terry, John Quentin and Tilda Swinton. First shown at the Venice Biennale and later as an installation at various museums of modem art around the world, this meditation on mortality was widely considered one of the filmmaker’s major artistic achievements. When it was shown on British television in September 1993, Channel 4 carried the image while the soundtrack was broadcast simultaneously on BBC Radio 3 – a collaborative project unique for its time.

Blue (1993)

Glitterbug, a collage of Super 8 footage from Jarman’s collection of videos and home-movie footage assembled by friends was released posthumously in 1994. It marked a fitting epitaph for a maverick British artist whose films, poetry, painting, collaborations with musicians and gay activism form an enduring and unique legacy.

Jason Wood

Jarman at HOME runs from Sun 30 Jan – Thu 10 Mar 2022.